Interview From Japan to North America Reverse Culture Shock

Carol Dussere interviewed Nik in 2016 about his experience in Japan. Originally published here, the below is that article.

From Japan to North America, Reverse Culture Shock

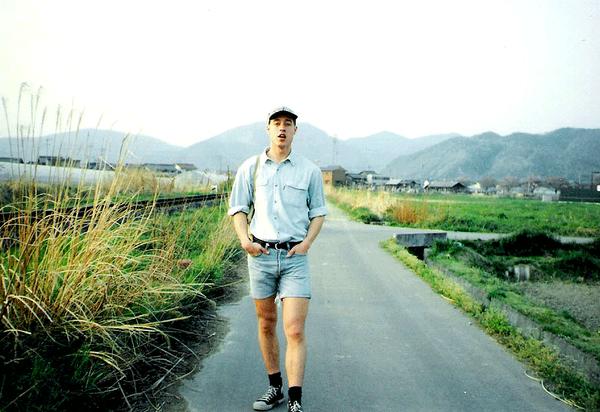

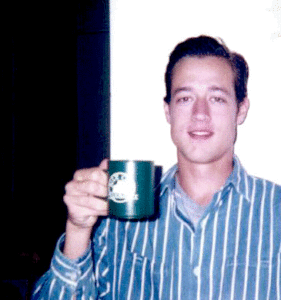

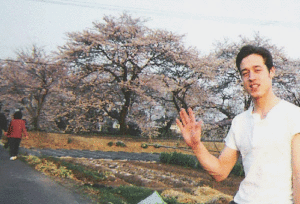

Nik is a Canadian who had three stints working in Japan for a total of twelve years: 1992-94, 1997-2003 and 2007-11. He is now living just outside New York City, where he’s working in IT. It’s a two-hour flight from his childhood home in Nova Scotia. I reached him from the Philippines via Skype. (Thanks to Nik for the photos.)

Nik’s story

In 1992, I went to Japan on a working holiday visa. The idea with this international exchange program was that young people could work abroad for a year in order to supplement travel costs and experience the culture. There were so few Canadians going to Japan that I was able to work for two and a half years as an assistant English teacher in both junior and senior high schools in the Gifu and Nagoya areas.

In 1997-2003, I worked with computer-related companies. I first had a job with a venture business trying to develop a competitive product to Java, and then an internship in database programming and software development. I worked in Nagoya for four years, then moved just outside the Tokyo area with my wife and two boys. On the third stint in 2007-11, I was an application support engineer with a US-based company. I had a side project of gathering all of the company’s knowledge and making it searchable through one knowledge-based search system. This system became so popular that the company transferred me to the NY office.

During my first time in Japan in 1992, I met a lot of foreigners who were teaching English while trying to get into graduate school in Japanese universities, where a lot of the reading and writing can be done in English. The undergraduate programs were all in Japanese. I met a guy whose Japanese was really just fantastic and who was enrolled in an undergraduate program. I wanted to do that too, but I found that getting into a Japanese program in the sciences was extremely competitive. Some students spent years in an endless state of trying to write entrance exams before finally getting in. There was also the expense. Japan was good for making money, but it was extremely expensive to study there.

So I decided to switch gears. I spent a year learning French and then went to the University of Montreal for computer science. However, I couldn’t shake my attachment with Japanese culture, so I lived in downtown Montreal with some young Japanese folks. My social life was mostly built around associating with Japanese people. One became my wife.

What drew you to the Japanese culture?

In learning basic Japanese and French, I discovered that Japanese people were quick to complement me, whereas French speakers would often snicker and tell me to speak English. So I guess the praise and the humility of the Japanese culture I found very appealing. I didn’t feel awkward about making mistakes. But I was also frustrated that I didn’t get corrections. I was attracted to the lack of sarcasm, which I found extremely refreshing, although after some years in Japan I learned about alternate ways to be insincere.

I also found a lot of ingenuity among technical folks, and I was attracted to the amount of detail Japanese engineers used in figuring things out. I really enjoyed working with the technical people.

In Gifu and Nagoya I felt extremely welcome, connected both with the foreign community and with my Japanese friends. This part of Japan was extremely warm and welcoming. My wife is from Fukuoka, and I enjoyed my visits there as well. In Tokyo I found that, because of the large number of foreigners, there was a wall between Japanese and foreigners and that the Japanese would push me over to the other side of it,

The only time I felt truly connected with Tokyoites was during the 2009 World Baseball Classic. I was watching one of the final games outside an electronics shop which had a huge television screen in the window. Quite a large crowd had gathered. Korea’s star pitcher had already dispensed with several Japanese batters. He was at the top of his game, and most betting people probably thought Korea was going to win. But then Suzuki Ichiro was up, and he hit the ball to allow Japan to win the championship. Everyone was overjoyed. Strangers were talking to each other and to me. It was a wonderful experience. Overall, if I were to live in Japan I’d choose western Japan, not Tokyo.

What about reverse culture shock?

I experienced reverse culture shock three times. When I returned in 1995 I felt extremely disconnected with my own culture and the people around me. I’m not a generally a talkative person, but in Japan I never felt socially awkward. There was always a basis for starting a conversation: how long have you been in Japan? what do you do? Among foreigners there was a camaraderie which I missed back home. I’d meet people who’d lived in another foreign country, and I could identify a bit, but there was never the same level of connection I had with my foreigner friends in Nagoya.

In November 1994, between Japan and Canada I went to Hong Kong. A café waitress serving my coffee just plopped the cup down on the table, and some of it sloshed over the edge. That would never happen in Japan, where coffee was carefully set down with two hands and without noise or spillage.

In North America everything felt a little bit raw or in-your-face. In New York ethnic restaurants with Spanish-speaking or Middle Eastern people behind the counter, I didn’t know how loudly to project my voice in order to be heard. A big one was interrupting people. In Japan people are very respectful about allowing others to speak. Of course in a senpai-kohai [superior-junior] relationship that could change. When I first came to New York, I was dealing with Israeli-Americans and an Israeli manager and coworker. I couldn’t get a word in.

In my own family, everyone interrupts. For me it was a psychological trigger back to my childhood. While I was in Japan my social skills with people in my own culture remained at a standstill. When I came back people would ask me about something they considered common knowledge, and I would have no idea what they were talking about. Like what happened to Seinfeld and Friends.

Then I might get asked, “Why don’t you know that?”

“Excuse me, but I’ve been cryogenically frozen for the past seven years.”

Some people would laugh, but at first they were definitely a bit surprised.

Once in Canada I asked a Japanese for a certain number of meters of network LAN cable.

He said, “Why are you asking in meters? You’re Canadian. You say ‘feet.’”

On the Internet, Japanese immigrants to Canada [who are undoubtedly struggling to become as Canadian as possible] would say, “You’re Canadian. You should know that.”

Canadians would just give me a funny look as if wondering whether I was really from there.

At the same time, my accent had mellowed out so I didn’t sound markedly Canadian. In the US a lot of people don’t pick up on my not being American right away. If they know I’m Canadian they expect me to know about, say, a well-known Canadian band I’d never heard of.

Going back to 1995 when I was 21 years old, at first I couldn’t identify culturally with a lot of people my age. But after maybe two or three months I discovered there were large groups of people who were actually very interested in Japan and maybe interested in going themselves. They wanted to ask about my experience. People were impressed when I spoke with my Japanese girlfriend and would come up and ask me questions. That was mostly in Vancouver, but in Montreal it happened as well. There it was awkward. I’d be reading a Japanese book on the Metro and people would ask in French what I was reading and where I learned Japanese. I wouldn’t be able to respond because my French wasn’t very good yet. Finally, I bought an Oxford guide to French grammar, read that on the Metro, and immediately people assumed I was a regular Anglophone learning French. They stopped talking to me.

Where there’s culture shock, there’s also culture benefit. Learning Japanese was the catalyst which led me to the career I have. It became my buki, my formidable or marketable professional skill immediately after I arrived in Canada. From then on I could always rely on my Japanese speaking ability as a tool I could use professionally.

During my first time in Japan, it seemed that the only Japanese people who wanted to talk to me were those who wanted to practice their English, while I was trying to practice Japanese. It was like a river of Japanese people coming downstream toward me while I was trying to get upriver.. I was dead-set on speaking only Japanese even though that probably meant closed doors and missed opportunities.

But there are well-educated people in Japan who speak educated English very well, so instead of having baby conversations in Japanese you can have intelligent conversations in English. There were also foreigners who were intellectually transferring their Western life to Japan while being well paid as English instructors or business people, so they had no incentive to learn Japanese.

What about the earthquakes?

About the Fukushima earthquake, on March 11, 2011, I was at work in Tokyo. I had experienced lots of smaller quakes. At first the shaking wasn’t scaring me even though most people were leaving, but one shake had such a depth that I thought that the building might come down. I was in the middle of the floor, probably the most dangerous place. Half or two-thirds of the computer monitors flipped over. There were no extremely huge tremors after that, but when I was outside I saw a lot of buildings swaying, which means they were probably more structurally sound. Our eight-floor building was not. The ones that just shake and don’t sway are the ones that crumble to pieces. I was extremely glad to be out of there. The most difficult part was that the tremors didn’t stop for days and even weeks. At night you couldn’t sleep. Every after-tremor might be the big one.

The earthquake was on Friday. For the following week we had a schedule of rolling blackouts to save power. On the Monday after the quake there was a sudden, nonscheduled power outage with a warning maybe an hour before. My company was figuring out whether people should go back to the office or not. I asked my manager if I could work remotely from Kyushu. The following Wednesday I continued working in Kyushu at my in-laws. Because of power outages in Tokyo I was the only Japan contact the American offices had. I was online and could tell the American office that the tsunami did not reach Tokyo, that it was just a sudden, unplanned power outage.

In Tokyo after the earthquake all of the convenience stores had nothing left to sell. The trains stopped running, but there were shuttle buses to the airport. As soon as I got to Kyushu, I found it surreal that it looked so totally unaffected. It was like night and day, although people were very concerned about the tsunami that hit Fukushima. Kyushu felt like a safe haven from the quakes. You may know that Kumamoto in Kyushu had an earthquake this year.

How did you adjust to Japanese working environment?

For several months in 1997 I worked in a smoking office. People were smoking right beside me. I found that extremely stressful. After some concessions I was allowed to move to a no-smoking floor. Once I was on the ferry from Kyushu to Osaka, and a Japanese gentleman came right up to me and asked what I found the biggest cultural difference between Japan and North America. I didn’t want to tell him it was cigarette smoke because he was smoking right in front of me and I didn’t want to make him feel uncomfortable. I just wanted to get away from him.

How about things, like the way the hierarchy functions and the way Westerners are treated?

Since I went to Japan at nineteen, in many ways I learned how to be a functional adult in Japan. Probably I would have had a different experience had I remained in Canada longer. That led to more culture shock in North America. In Japan the pecking order is very clearly defined, including linguistically. When I learned Japanese–and I think a lot of foreigners do the same thing—I imitated the way people spoke to me, so if they spoke to me in honorific Japanese I would reply to them in honorific Japanese. If they spoke to me in plain Japanese, I would reply in plain Japanese. This can be awkward. If you establish a relationship with your company president and four months later you realize speaking plain Japanese to him is totally inappropriate, what do you do? Switching over is also stressful. So even though my language with the company president was wrong, I continued using it with him because of the rapport we’d established. It was the same with friends I made early in Japan, people I spoke to in English. Sometimes they would go away for a year. By the time they came back I was already comfortably speaking Japanese, but because our rapport was already established in English, I would revert to English with them.

After many years in Japan I did discover that not everybody followed the rules. There are people who may be at various places on the Asperger’s scale, who don’t pick up on social cues the way 99% of their fellow Japanese do, and so they speak in rough or inappropriate language. They just get segmented out so they aren’t forefront in social situations. They aren’t trusted to deal with customers, but are put in a back room. Not picking up on the cues doesn’t necessarily mean being ostracized. They’re just treated differently.

It’s the same with foreigners. I remember reading—I think it was a guide to etiquette–advice against trying to be Japanese because it would only confuse people. Just use your best Western etiquette. A book like that was written for Western business people, not a kid of 19 who was trying to immerse himself in the culture. I probably did end up confusing people by trying to act Japanese, to the point where I did actually begin to develop something of a Japanese persona.

How did you find moving back to a Western workplace?

I came to really appreciate a lot of aspects of Japan. In the US, and probably in Canada too, there’s a bit of a fight-or-flight phenomenon in the workplace and in personal relationships. In Japan there’s a group mentality, along with the concept of dealing with a problem until it’s resolved, although younger Japanese businesses don’t necessarily operate this way. Traditionally, a problem is handled within the group. That includes how to deal with an employee who can’t be trusted with business decisions anymore. The idea is they don’t fire people. Lifelong employment is not a business policy but a social dynamic. The first impulse is to restructure the group in a way that works for the group, not to get rid of the guy.

Anything that you want to talk about that I haven’t asked?

Just that what’s going to happen in the future is anyone’s guess. In some ways I was disappointed that Japan lost the mobile phone race. They were the first to introduce color liquid crystal screens and to make smartphones. Then US companies like Apple and Google came and took their lead away. Japan has a way to go in terms of learning how to innovate and improvise. They’re a great culture in terms of following established formulae, but not in coming up with new ideas. I hope it finds a way to reinvent itself. But with China as the world’s number two economy, I think I’d tell young people they’d be better off learning Chinese.

Would you like to move back?

Not at this stage. My wife and I would be interested in retiring there. There’s a lot we love about Japan. Right now we’re pretty happy in the US with our three boys.

A reader writes:

Interesting story about Nik and his Japan experiences, especially now that I’m in Tokyo for a short vacation far from his extensive stories however. Great read just the same and an eye-opener for many.